Tag Archives: food

On Gourmet

When Detroiters walk into Astro Coffee, it’s not uncommon to see a first-time patron walk up to the counter, look up at the menu, and say something like “I don’t want the gourmet coffee; what’s the regular one?” Or conversely, it’s easy to stroll the aisles of a supermarket and see trail mix, pasta, or hot dogs branded as gourmet products.

Context is everything. A word so over-utilized can only derive meaning from a group of people with a shared understanding of its meaning. It’s probably, then, the case that people who appreciate cuisine and its place in the world also can appreciate some elements of its history and even its lexicon.

Much like food and drink, language focuses a powerful lens on the unique aspects of a given culture. So it should be of little surprise that gourmet, one of our most enduring terms for describing those of discerning taste, is derived from French. It seems suitable that a country capable of producing burgundy and inventing Bearnaise should have coined a term for appreciation of delicacies that’s lasted almost 200 years and across languages.

Perhaps the most well-known gourmet since the term came into popular usage was Jean Brillat-Savarin. His 1825 book The Physiology of Taste is widely regarded as the archetype for the contemporary food essay. Written in French and later widely translated, it was released only five years after the earliest use of the term in English as cited by the Oxford English Dictionary (OED).

Among his numerous opinions, Brillat-Savarin comes to the conclusion that “Those persons who suffer from indigestion, or who become drunk, are utterly ignorant of the true principles of eating and drinking.”

He’s drawing the distinction between gourmand and gourmet, between those who over-eat and those who enjoy quality. Interestingly, the former is a much older term: The OED cites an early written usage of gourmand in Vitae Patrum by English merchant William Caxton in 1495. While the two are often used interchangeably today, the two are, in fact, historically unrelated.

Derived from Old French words groumet and grommes meaning “manservant,” the term gourmet grew in Middle French to describe specifically the role of a wine valet, an attendant who understood the full range of wines’ properties. Such a servant was skilled, able to quite possibly discern a wine’s characteristics and origins from smell or taste.

While the OED hints that there may have been some earlier cross-pollination between Germanic languages and Old French, other sources are more confident in the connection. Some speculate that the root of the word groom, the Old English grōma (meaning a male child), was incorporated into the French language, initiating the evolution toward gourmet.

Of course, all that said, people were celebrating great food long before French aristocrats were training young men to sniff their wines for them.

Epicurus, the Greek philosopher, is the inspiration for English words epicure and, now, modestly clever combinations of words like “epicurious.” Today, Merriam-Webster defines an epicure as “one with sensitive or discriminating tastes,” a definition strikingly similar to that of a gourmet, though it also lists an archaic definition for one devoted to sensual pleasure.

It seems that this misconception of Epicurus as an unabashed hedonist emerged from something of a smear campaign against his name. While he is now widely acknowledged for having lived a modest life, his philosophy of simple, virtuous living leading to absence of pain or suffering was rooted in an atheistic worldview that eschewed an afterlife. Such thinking was clearly considered dangerous by many Christians throughout their own early history. Indeed, a derivation of his name came to be synonymous with heresy in early Christian cultures, and its earliest usages in English relate as much to religion as they do to food: Thomas Cooper, bishop of Winchester, lamented in his 1859 An admonition to the people of England that “The schoole of Epicure, and the Atheists, is mightily increased in these dayes.”

Still, throughout the 1600s and 1700s, his name was synonymous in some English-speaking circles with dainty, thoughtful consumption of delicious food, meaning that despite its confused origins, it pre-dates gourmet in its conveyance of this concept.

In the 20th century, though, there can be no doubt that “gourmet” came to symbolize all the finest things in the culinary realm. Even the magazine, Gourmet, that carried the term on its cover for seven decades is something of a metaphor for the word itself. When it debuted in 1941, Gourmet was the pinnacle of food magazines. While its primary competition was printed in black and white on newsprint with more modest recipes on its pages, Gourmet aimed to bring haute cuisine to its readers and itself embodied the spirit of the finer things, printed in color on glossier paper. Critics like James Beard reviewed restaurants in fashionable locales, and French cuisine was prominently featured.

But by the time the 90s came about, can anyone say that Gourmet carried itself differently than any other magazine? Scanning the shelves at a book store, it blended in among the dozens of new periodicals. Instead, it was larger, denser, more serious publications that came to earn respect, like Gastronomica or The Art of Eating. While Ruth Reichl, editor for the last years at Gourmet, managed to feature spectacular writing (look no further than getting David Foster Wallace to write about lobsters), the image of the magazine became confused: It sat next to bubble gum on store shelves, and in an effort to capture younger readers content was no longer solely aimed at the white linen crowd. Conversely, in its earliest history, there was a clear audience: It was reserved for those who cared and, frankly, probably those who had the means to care.

It’s a decent parallel. Just as the Gourmet brand saw itself diluted in a sprawling, re-emergent American food culture, the term gourmet has ostensibly lost its value with every package of preservative-laden, gourmet-labeled product that came to grace grocery store shelves. If everything is gourmet, then nothing is.

That said, with 200 years of history behind it, there’s still a case to be made for gourmet as a valued part of our cultural dictionary. After all, in context, it still has meaning. And among people who do truly care about what they’re eating, it can retain that meaning, the one and the same about which Brillat-Savarin wrote 200 years ago. At the very least, I’m sure everyone can agree it’s more appealing and more appropriate than foodie.

Hippo’s — An Occasional Coney Dog Alternative

Ask any local what singular dish is quintessential Motor City snacking and their likely answer is the Coney dog. Whether you’re feeble with a hangover or just plain hungry for a big plate of unhealthy, there is nothing quite as satisfying as a natural casing hot dog slathered with beef heart chili, minced onion and yellow mustard in a spongy, white-bread bun. It’s a dog remarkably impractical to eat with your hands. In fact, if you can pick it up without making a mess of yourself, you might as well call it a chili dog.

But on the rare occurrence you might feel like a change, look no further than Chicago. Actually, Chicago is kind of far, so look no further than Rochester Road, slightly north of Maple, for a Hippo Dog.

Hippo’s crafts an authentic Chicago-style dog. It starts with a steamed, Vienna Beef wiener resting in a poppy seed bun and then “dragged through the garden” by topping with mustard, onion, shockingly green sweet pickle relish, a dill pickle spear, tomato slices, sport peppers and a dash of celery salt. It’s a heady combination of soft, warm, comforting, crunchy and fresh. Don’t even think about ketchup. Save that for your fries.

Hippo’s crafts an authentic Chicago-style dog. It starts with a steamed, Vienna Beef wiener resting in a poppy seed bun and then “dragged through the garden” by topping with mustard, onion, shockingly green sweet pickle relish, a dill pickle spear, tomato slices, sport peppers and a dash of celery salt. It’s a heady combination of soft, warm, comforting, crunchy and fresh. Don’t even think about ketchup. Save that for your fries.

Like many of Chicago’s hot dog stands, Hippo’s is spare on the inside. Seating consists of a counter that runs along two sides of the building beneath large windows. Walls are adorned with accolades, signed photos of local news celebrities and nods to the Windy City. Bright yellow is the color scheme. During the busy weekday lunch hour, it’s not uncommon to see toolmakers rubbing elbows with mid-level executives. The cheerful staff is always ready with a greeting, and there’s a stack of newspapers near the door if you like to read a bit as you lean into your lunch.

In addition to a diverse menu of other styles of hot dogs (including the Coney), you can chomp a char-broiled Polish Hippo, Cajun sausage, Italian sausage, bratwurst, a Maxwell Street Polish sausage covered with grilled onions or a Chicago Avenue Polish sausage complete with sauerkraut and a pickle. Hippo’s has an entire library of tube steaks, most of which cost less than four bucks.

But the real draw is the classic Hippo dog for only $2.15. Being a Detroiter, there is no way I could ever admit that a Chicago-style hot dog is somehow superior to a Coney, though it is nice to have a place like Hippo’s around for an uncommon diversion.

Hippo’s is located at 1648 Rochester Rd. in Troy and a newer location at 35520 Groesbeck Highway, Clinton Township.

You Will Like Cauliflower Now

Cauliflower is one of those foods that a lot of people in their 30s seem to have loathed as a kid, right alongside brussels sprouts, beets, cabbage, and the others in the Pantheon of Vegetables Rejected by Parents in the Eighties. My mom thoughtfully coated her oft-steamed cauliflower in generous doses of butter (then margarine, then “Smart Balance,” then… well, you get the idea), so I never hated it – but I never really liked it.

Until a few years ago.

My friend Noelle has written about a similar transition she made as a result of some cauliflower I made at a dinner party about a year back, and I have to say, that recipe is still one of my own favorite ways of preparing it. I decided to make it tonight, so despite our somewhat unintended decision to not frequently do recipe write ups here, I’m throwing down a recipe post.

Ingredients

- Shocker, I know, but you need a head of cauliflower

- A tablespoon or three of capers

- 1-3 medium sized cloves of garlic to taste

- 2+ tablespoons olive oil

- 2-3 table spoons white balsamic vinegar… or not.

Note: Any white vinegar can do here, but the higher the acid flavor, the more you might need to cut back on it or add more oil to diminish the intensity. I’d even so far as to add a pinch of sugar if it seems too bright. - Salt and pepper

Cookery & Shit

- Fair warning: I don’t generally measure anything except when baking or making ice cream, so the quantities here are kind of made up.

- Pre-heat the oven to 450 F

- Cut or pull the cauliflower apart into florets. Not too small, or they just get soggy between the long cooking and the dressing later.

- Toss it in olive oil inside a baking pan of some kind until gently but entirely coated.

- Roast the veggies for about 15 minutes or so, pull them out, toss them around a bit, and get them right back in there for another 10-15 minutes.

- While that’s cooking, mince the living shit out of that garlic. I mean, cut that up like the garlic ran over your dog or your sister or something. It’s not getting cooked, so fineness is key. And use less if you don’t love garlic. (Duh.)

- Mix the garlic in a bowl with the remaining olive oil and the vinegar. It should be a bit acidic but, especially if using the balsamic, very round in flavor. This part is really just a balancing act, and you need to balance it to your taste.

- Mix in the capers. I use a fairly immodest palm full of the little guys because the briny flavor is what actually makes this whole dish go. But whatever you want.

- Season the dressing with salt and pepper.

- When the cauliflower’s done, toss it with the dressing.

Words of caution: (a) Don’t toss it too much because the capers will fall to the bottom of the bowl, and you want to EAT THE CAPERS because they are DELICIOUS and (b) don’t use all the liquid dressing if it looks like it’s too much. I mean, that’s obvious, but still. Soggy cauliflower is sad cauliflower. - Serve it up to your guests, who will probably take one little floret just to be polite, and then they’ll eat it, say nice things to you, and take more. (If that doesn’t happen, you have quite probably screwed the whole thing up.)

I wouldn’t be so brazen in extolling the virtues of this super simple cauliflower dish except that: (a) Noelle and about 4 other people really, really seemed to like it, so I know I’m not alone, and (b) I realized in trying the cauliflower at Girl & the Goat that the principle behind this is really quite sound: roasting earthy veggies and giving them bright accent flavors kicks ass. Mine is nowhere near as good as Stephanie Izard’s, of course (she puts pickled peppers and mint in it… mad genius) but it has the same general idea behind it. And it’s a good fucking idea.

Hope you actually enjoy it as much as I do! Now I’m going to finish my delish Beaujolais. How’s that for a Wednesday?

A Genuine Slice

Master pizzaiolo Dave Mancini’s move from a comfortable career as a physical therapist to serving what is arguably the best pizza in Detroit has been well documented. But it was no easy journey. It took hard work, passion, persistence, and an enduring love for the city to make it happen.

“You can’t hide behind the cheese”

What makes Supino pizza so good? It isn’t some flawless recipe handed down by Mancini’s Italian ancestors or discovered in an ancient Roman text. The secret to his success is nothing more than a focused effort to make the best possible pizza that he could. In fact, it took about seven years from the time he started making pizza to the eventual opening of Supino.

“I researched the shit out of pizza,” he says. To learn the business model, on his Saturdays off, he worked in a Birmingham pizzeria. He bought every recipe book he could find, even purchasing entire books for just one pizza recipe. After struggling with a few variables in the crust that he just couldn’t get a handle on, he did some consultation with a former pizzaiolo at Boston’s renowned pizza joint, Santarpios, until he got the consistency that he was looking for.

“A pizza is never really better than its crust. You can have amazing toppings and amazing sauce but if the crust is mediocre, the pizza is going to be mediocre.”

Regular patron and pizza aficionado, Phil Spradlin, tends to agree. He only orders his pizza with cheese because, as he tells Mancini, “You can’t hide behind the cheese.”

Regular patron and pizza aficionado, Phil Spradlin, tends to agree. He only orders his pizza with cheese because, as he tells Mancini, “You can’t hide behind the cheese.”

The question of style comes up more often than Mancini would care to address. “It cracks me up when I hear ‘New York-style pizza and New Haven-style pizza’, he says. “There are so many variations within those subgroups. Even between those two there is overlap. If you go to New York and get pizza at six different places, they are going to be pretty damn different. They’re not going to be Detroit-style, like Buddy’s, or Chicago-style. You can probably find those in New York but when people talk about New York-style pizza they aren’t pinning down a specific process. Most of them have a thin crust and are 18-inch pies but other than that, they’re kind of their own thing.”

He gets New Yorkers that come into the shop with a broad range of opinions. Some of them will tell Mancini that the pizza is just like home, some of them will tell him that it’s not really like home but it’s good enough, and some of them will tell him that it’s better than home.

Ask Mancini what style of pizza he makes and the short answer is “Dave’s style”.

Detroit Synergy

Local media make a big deal when celebrity chefs open upscale restaurants in Detroit. These successes certainly foster a positive perception of dining in Detroit, both locally and nationally. But it’s just as crucial – some would say even more so – for the resurgence of the city that small, independent establishments take root in their respective communities and be more than simply a place to eat good food.

For Mancini’s part, he’s doing what he can to help other promising food businesses by using their products and sometimes even opening his kitchen to them. You can order Katie’s Cannoli, hand-filled at the time of order so the shell stays crisp, for dessert. Porktown trades a portion of their sausage for use of his kitchen and Mancini purchases more for his pizza. The Asian inspired pop-up café, Neighborhood Noodle, operated out of Supino for a few of their monthly gigs.

He seems almost embarrassed talking about the role he plays in this culture of cooperation, and believes he sometimes gets too much credit. Mancini recognizes that he’s certainly not the first one to think of mentoring other food entrepreneurs and is quick to praise those that have come before him and have helped him get his own business off to a strong start.

He seems almost embarrassed talking about the role he plays in this culture of cooperation, and believes he sometimes gets too much credit. Mancini recognizes that he’s certainly not the first one to think of mentoring other food entrepreneurs and is quick to praise those that have come before him and have helped him get his own business off to a strong start.

Like Jerry Belanger, owner of Park Bar, who would come in and order fifteen pies to hand out to his customers and give Supino a boost in its early days after opening. Spirited restaurateur Torya Blanchard helped to get Supino featured in Delta Sky Magazine. When Mancini decided he wanted to serve beer, Dan Scarsella of Motor City Brewing Works consulted with him, knowing the two businesses might be in direct competition.

Even neighboring Russell Street Deli would hand out menus to their customers during the lunch hour, apparently unconcerned about the possibility of losing customers. Mancini maintains that this cooperative culture “especially plays well in Detroit, because we’re underserved”.

He recalls the recent food truck gathering in Shed 2 of Eastern Market and how he was slammed with customers the entire time just because the event drew hordes of hungry people. Though some of his friends in the restaurant industry bristle about the possible competition with food carts, he believes that Detroit is a long way away from worrying about this kind of rivalry for the dining dollar.

Eastern Market on the rise

Eastern Market wasn’t the first location Mancini thought of when looking for a building to house Supino’s kitchen. It was only after an extensive three-year search, underscored by negotiations with indifferent landlords that had no interest in taking any risk by repairing the spaces they owned, that he “fell backasswards” into his current location.

Mancini finds far more advantages than challenges being based out of the Market district. Though all the buildings are old and there is always something that needs repair, that’s more than made up for by the steady foot traffic from the Saturday market, folks from downtown coming in for lunch on the weekdays, and other food workers in the neighborhood. “I think people with a good food idea are crazy not to jump into the Eastern Market area,” he says. He especially thinks that a good bistro and brewpub would do well there.

Mancini has no plans to open a new location any time soon. He’s not the type to risk the quality of his product to cash in on its popularity. But there will be some changes this year.

Mancini has no plans to open a new location any time soon. He’s not the type to risk the quality of his product to cash in on its popularity. But there will be some changes this year.

He is consulting with local drinks authority, Putnam Weekley, to bring in a beverage program. Soon you’ll be able to order a beer or inexpensive glass of table wine chosen specifically to pair with the pizza. He also envisions a small, European-style bar with plenty of apertivi, digestivi, and a modest liquor selection. He speaks enthusiastically about Amaro CioCiaro, a bittersweet Italian liqueur produced in the same region as the town of Supino, Italy that he noticed one night while drinking at The Sugar House.

But instead of rushing to sell booze and maximize profit, he’s carefully planning how and what to introduce into the menu and ensure the core of his business stays healthy. While unsexy in comparison to a San Gennaro pie straight from the oven, all of this methodical planning and attention to detail is fundamental to Dave Mancini’s success, and makes certain that Supino will remain a fixture in Detroit for a long time to come.

The Brinery’s New Turnip Pickles

Ann Arborites have been able to sink their teeth into the naturally fermented products of The Brinery for some time. David Klingenberger, owner and crazy mad genius of the old school lacto-fermentation process, has been selling at the Ann Arbor farmer’s market and working with Washtenaw County restaurants. Thankfully, he’s now at Eastern Market and those of us a little closer get regular access to his goods.

His most recent offering is made from a turnip of Japanese origin. And it’s amazing.

Hakurei turnips (pronounced, as I understand it, hah-kur-eye) are, in Klingenberger’s words, “the honeycrisp of turnips” — sweet, crisp, tender, and juicy. He’s routinely made turnip pickles in the past, and they’re perfectly delicious with a nice earthy flavor and cut thickly for a nice combination of chewiness and crunch. It is evidently the ideal turnip for consuming raw and doesn’t even require peeling, a notion espoused by plenty of blogging salad lovers.

Given The Brinery’s natural fermentation process whereby the raw veggies are preserved by bacteria (rather than by cooking and vinegar), these would seem to be pretty well suited to pickling.

And indeed, they are: Their new Hakurei-based pickles are shaved exceptionally thin and remain quite crunchy. Klingenberger sources these from Ann Arbor-based Garden Works, a certified organic 4.5-acre truck garden and greenhouse farm, but the turnip is a hybrid developed in Japan in the 1950s.

The pickles are irresistible on their own, or throw them on a little baguette sandwich if you can keep your hand out of the jar. Fans of fermented goods can pick them up on Saturdays at Eastern Market or check out where David will be selling his products next at The Brinery’s website.

Season’s Greetings

Has there been, in recent memory, a better Detroit holiday season for food lovers and gluttons than this December? Hackneyed as the sentiment may seem, this has already been a pretty joyful, stirring month.

There was pleasure and even inspiration to be had from watching people coming together for the 2nd annual Detroit Holiday Food Bazaar and from talking to people who were just discovering that interesting things are happening with food in Detroit. And it was legitimately fun to see old friends hanging out, new friends being made, and small business owners connecting with one another over pickled turnips and tequila at the Sugar House.

The sentimental fool in all of us has to derive some sense of satisfaction from watching much of Detroit’s gastronomic community enjoy not just each other’s products but each other’s company.

That’s all a long way of saying that the holiday season is off to as fine a start as one could hope for.

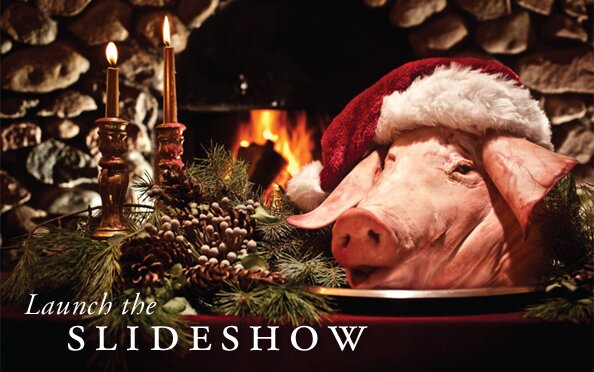

In case you missed either event, we’ve put together a little slide show of both, which begins with a special holiday greeting card, Gourmet Underground Detroit style. Best wishes for a wine-soaked end to 2011 and a pork-filled 2012.

Second Annual Detroit Holiday Food Bazaar

Don’t miss Detroit’s premier pop-up holiday marketplace featuring a variety of independent food vendors on Friday, December 9, 2011, from 5:00pm until 11:00pm.

In its second year of operation, the Detroit Holiday Food Bazaar has expanded and moved to the historic Eastern Market District. The list of vendors includes: Leopold’s Books, Love’s Custard Pie, Drought Juice, Detroit Institute of Bagels, Miette, Pete’s Chocolate Co., El Azteco, RG Distribution, Hugh, The Rogue Estate, Perkins Pickles, Beau Bien Fine Foods, Native Kitchen, Al Meida, Marvin Shaouni Photography, Great Lakes Coffee Roasting Company, McClure’s Pickles, Simply Suzanne, Suddenly Sauer, Corridor Sausage Co., Gang of Pour, and Porktown Sausage.

Not only is this a good way to support local small businesses and startups, you’ll have the opportunity to purchase some of the most finely crafted food products available in our city.

Ink it on your calendar and RSVP to their facebook event page.

Second Annual Detroit Holiday Food Bazaar

Friday, December 9, 2011

5:00pm until 11:00pm

2448 Market Street Detroit (above Cost Plus Wines)

How to Make a Meat Head

The concept is simple – drape thinly sliced, cured meat over a skull. But in case you are wondering how we made ours, here is the step-by-step process:

Step 1. Adhere a washed, plastic human skull to a serving platter using hot glue or nails. You can find plastic skulls in any large department store. Ours was produced by artisans in Shenzhen, China.

Step 2. Drill small holes into the center of the eye sockets sized to accept toothpicks. Alternatively, you could hot glue toothpick pieces to the eye sockets.

Step 3. Make the eyes using cocktail onions with embedded olives for the pupils. Attach to the toothpicks in the eye sockets. Pimento stuffed olives or those nuclear-colored maraschino cherries would work too.

Step 4. Drape skull with meat. Thinly sliced prosciutto works well. Something more red in color like hot capicola or chorizo would be cool. Make sure it’s sliced thin. Fat helps the meat stick to the skull.

Step 5. Add cheese, crackers, olives, or whatever you normally add to a meat and cheese platter.

Step 6. Enjoy!

Bitter Melon

Every Saturday for a couple summers in a row now, I’ve gotten herbs, baby bok choy, beans, and other greens from Vang Family Farm at Eastern Market. And every Saturday, I stare quizzically at the bumpy “Bitter Melon” bundled into packs of three with a rubber band and stacked neatly at the end of the table.

No longer.

Drawn in by its strange appearance — it looks like a brain mated with a cucumber — I bought my first bitter melons last Saturday. Not knowing where to begin, I took to the internet, where I discovered this particular gem:

Stir fry seemed like an easy, ideal preparation for my first foray into bitter melon, so a few days later, I surveyed the fridge and decided on a bitter melon stir fry with egg, shrimp, onion, garlic, and ginger. Aiming for something a bit more “Thai” tasting, I threw together a “sauce” of tamarind paste, fish sauce, soy, rice vinegar, siracha, and sugar.

Everything I read indicated that scooping out the spongy interior and the seeds was a “must,” but opinions were divided on the notion of parboiling or steaming the melons for a couple of minutes to remove some bitterness before frying. I figured I’d start out with the unadulterated melon, so we fried them without any prior heat treatment.

Accurately named, bitter melon is remarkably bitter. It’s not at all sharp like a grapefruit or charred like some coffee. Rather, it has a sort of dull, earthy, chalky bitterness that reminded me of a beer flavored excessively with Chinook hops. Larger pieces (and/or pieces with some of the white interior still clinging to the fruit) seemed to retain more bitterness throughout the process, which made sense.

We served it over rice and with some fresh cilantro on top, both of which were fine compliments. Next time, I might consider using pork to get some extra fat to help buffet the bitterness back a bit. That seems to be a common recipe combination for bitter melon online, and it certainly would hold back that chalky flavor more than shrimp and siracha.

Regardless, the bitterness after stir frying isn’t overwhelming by any stretch. I can understand why people sweat it with salt and cook it before completing the stir fry, but even without those measures, the bitter flavors are simply intense, not offensive.

While there appear to be no studies to corroborate the claims, many Asian countries ostensibly consider this fruit to be quite healthy. Regardless, while I’m in no rush to add bitter melon to my list of staple ingredients, I’ll be trying to use it more in the future. It’s truly unique and unquestionably interesting.