Monthly Archives: November 2011

Gourmet Underground Detroit's content archives are organized by date and catalog the aggregated content of our Features pages as well as our blog.

Mocha Flip

Ever want a nice silky mocha when all you have is rum? Happens to me all the time. And everyone else too, I’m sure. Here’s the solution.

Mocha Flip

- 2 oz El Dorado 12 year aged rum

- .5 oz creme de cacao

- .5 oz coffee syrup*

- .5 oz milk

- Whole egg

- A chunk of dark chocolate

- Chocolate bitters (optional)

Dry shake the first 5 ingredients. Add ice, shake, and double strain into a cocktail glass. Dash chocolate bitters on top. Use a microplane or grater to grate some dark chocolate over the top of the drink.

* – Make coffee syrup by combining equal parts brewed coffee and sugar in a bottle larger than the combined volume and just shaking (for a long while) to combine. It’ll last in the fridge for quite a while. Use a lighter roast or cold brew to minimize bitterness. (A coffee liqueur could be used instead of this, but it’d have to be exceptionally high quality or homemade. Use Kahlua in cocktails at your own peril.)

Second Annual Detroit Holiday Food Bazaar

Don’t miss Detroit’s premier pop-up holiday marketplace featuring a variety of independent food vendors on Friday, December 9, 2011, from 5:00pm until 11:00pm.

In its second year of operation, the Detroit Holiday Food Bazaar has expanded and moved to the historic Eastern Market District. The list of vendors includes: Leopold’s Books, Love’s Custard Pie, Drought Juice, Detroit Institute of Bagels, Miette, Pete’s Chocolate Co., El Azteco, RG Distribution, Hugh, The Rogue Estate, Perkins Pickles, Beau Bien Fine Foods, Native Kitchen, Al Meida, Marvin Shaouni Photography, Great Lakes Coffee Roasting Company, McClure’s Pickles, Simply Suzanne, Suddenly Sauer, Corridor Sausage Co., Gang of Pour, and Porktown Sausage.

Not only is this a good way to support local small businesses and startups, you’ll have the opportunity to purchase some of the most finely crafted food products available in our city.

Ink it on your calendar and RSVP to their facebook event page.

Second Annual Detroit Holiday Food Bazaar

Friday, December 9, 2011

5:00pm until 11:00pm

2448 Market Street Detroit (above Cost Plus Wines)

The Science & Art of Espresso

A moment or two after sliding the lever on his Synesso espresso machine to the left, a rich, dark, wood-toned liquid poured from the two opposing spouts at the bottom of the portafilter and ran smoothly into the tiny cup below. Staring at it intently, Dai Hughes commented, “It’s ideal when it pops out and hugs back in a bit, so it kinda gets that hourglass shape. It’s a very feminine shape it’ll take on.”

Dai, owner of Corktown’s Astro Coffee, is describing the appearance of his ideal espresso, a particularly rich, saporous shot. Whereas a traditional, Old World barista may aim, no matter the bean, for a fairly consistent bitterness and flavor, Dai and his contemporaries are generally striving to emphasize unique flavors within particular blends and beans.

Espresso is a finicky product, and I had been curious how he goes about crafting what is arguably the best tasting espresso in southeast Michigan. He invited me behind the counter to get a first-hand look.

Before pulling that first shot, Dai describes the myriad variables at play. “When I started [as a barista], our parameters were the coarseness of the grind, the dose, and the tamp [of the grounds in the filter],” he says. “Then we introduced controlling the temperature. And what people were saying is that machines were set at their golden temperature… but what if beans were suited to different temps?”

Today’s routine actually begins with that adjustment. “I’m using the Owl’s Howl, which is the last thing I used the last time we closed, so there’s at least some familiarity,” he says, referring to having a recent reference point to the beans he’s placed in the grinder. We peer underneath the three-headed espresso machine to see the temperature controls. He left the day before with the temperature set to 200.5 degrees. Thus to get an idea of the flavor within a wider range, he sets the first group to 200 and the second to 201.

After running several doses of beans through the grinder to clear it of the previous day’s now-oxidized coffee, he runs the first shot, which we won’t bother to taste, and looks to see if it runs out of the machine with that hourglass shape. Before measuring a single thing, he’s both seasoning the machine and checking to see if he’s near that ideal viscosity. We’re in the ballpark, but, he notes, that’s not always the case: “You can come in, especially if you’re switching to a new espresso, and the thing is just pissing out or it’s ‘drip, drip, drip.’”

Dai grinds another dose and puts it on the scale. His first measurement shows the grounds weigh just over 17g. He makes a shot and measures the resulting liquid at over 27g.

“I’m collecting information at this point,” he says, “but we’ll taste this one to understand where we’re at.” We taste it, and it’s thin. He pulls another at the higher temperature, and it seems as though it may be thicker in body but definitely more astringent.

The grounds for our third shot weigh in at 19g, he sets the temp back to 200.5, and the shot itself comes in at around 25.5g – a dry-to-wet comparison of about 74 or 75%, which is closer to Dai’s ideal range. It’s delicious.

For many baristas, these types of ratios and measurements guide the ideal shot. This is an area where Dai has a philosophical difference with many of his fellow baristas: At this point in the process, he’s starting to let his experience and his taste buds drive the decision making. He’s after a balance of fruit and acidity – an explanation which elicits a grin from me because it’s a concept to which anyone that has made a cocktail or uncorked a bottle of cru Beaujolais can relate.

“Part of it is knowing that things can change… especially right at the beginning. Temperatures are changing, the door is swinging open, it’s hot, it’s humid,” he laments. But in this case, without even adjusting the grinder, the dosing of his grounds has settled out at a dry weight of 19g. He tweaks the temperature again, up to 200.7 degrees, and we try another shot.

“Part of it is knowing that things can change… especially right at the beginning. Temperatures are changing, the door is swinging open, it’s hot, it’s humid,” he laments. But in this case, without even adjusting the grinder, the dosing of his grounds has settled out at a dry weight of 19g. He tweaks the temperature again, up to 200.7 degrees, and we try another shot.

This one is, to Dai’s taste, pretty much ideal. The flavor is true to his objective – ripe, berry-ish, thick, and a bit tart. But he emphasizes that others may prefer the shot pulled at 200.5 degrees instead. Or even something else entirely. And of course, he notes, the prevailing opinions among coffee wonks everywhere change frequently: “There was a period of time when over-dosing was cool… and you do a coarser grind with more in it. But… this is going to change in three months. Someone will have written a new guide.”

Even the parameters of what baristas can control are in flux. In addition to grind, dose, temperature, and so on, companies have introduced machines with pressure controls. “Then the pressure profiling systems came, and you just have so many parameters,” he says with a bit of skepticism.

For Astro, the constant is ostensibly Dai’s sense of taste.

“We’re dialing in to this range of comfort, and from there, the micro-adjustments – temperature or, at times, grind on the collar [of the grinder] and things like that – we’re going to make those on the fly and then taste. It’s good to know these other kinds of things, but it’s good to taste. You can have all the ratios in the world, but there are all these other factors.”

Dai honed his skills – and his taste buds – at London’s Monmouth Coffee, an early pioneer in today’s culture. “Coffee culture is really young… but it has changed so rapidly in the last 5 to 10 years. So what you see here, it wasn’t like this at all.” Still, founded in 1978, Monmouth practically invented the concept of “direct trade,” and Dai – admittedly a coffee neophyte before he began working there – got his start in that knowledgeable environment.

Having experience from an older, established shop seems to offer him perspective: “Imagine if you were apprenticing as a brewer,” he posits, “what they teach they might also tell you is the law or the only way to do it. But it’s not. Have you ever had two IPAs that are exactly the same? No. And if I order a shot somewhere else, I don’t want it to taste exactly like mine.”

Rather than touting the next big machine or adhering to the newest geekery-inspired guidelines, he seems focused primarily on giving customers a pleasant experience and letting his expression of the innate, delicious flavor of his product do the talking.

He motions toward the four espresso cups from which we’ve tasted and says, “You’ve probably tasted all those shots in your life – or even just here. Underextracted, overextracted… an espresso is the highest error drink we can do. At some point, put your books away, put your refractometers away. This is something, like wine, that’s constantly changing.”

We finish tasting that final shot and he adds, “I don’t think you can truly enjoy it until you respect that.”

Drunken Angel

Coconut syrup was one of my primary cocktail revelations of the last year. It’s a flavor that generally evokes in me an absolute numb, deadened sensation. Total ennui. It’s not that I hate coconut: I just don’t like it, and it’s never done much for me.

But last January or so, I had some ideas for drinks based off of coconut ranging from mixing it with rum and Aperol to using it in an egg white foam atop bourbon and chocolate bitters with fresh chocolate for sort of a German Chocolate Cake flavor. I found earlier this month that I, much to my surprise, missed having coconut syrup around.

So I made more and decided to start making drinks based upon it again. Of all the cocktails I’ve made recently, this is surprisingly my favorite, a nicely balanced drink that really only hints at coconut. The absinthe rinse is crucial: Minus that component, this particular recipe comes off as a just a touch flabby. Somehow, the absinthe highlights the citrus without adding much of the characteristic anise/licorice flavor. Pretty much awesome.

I’m calling it the Drunken Angel. Here’s the recipe.

Drunken Angel

- .75 oz aged rum (not too flavorful – in this case, I used Appleton 12)

- .75 oz white rum

- .75 oz lime juice

- .5 oz yellow chartreuse

- .5 oz coconut syrup

- Absinthe

- 1 egg white

- Peychaud’s bitters

Combine all the ingredients save the bitters in a shaker. Dry shake. Shake with ice. Swirl a bit of absinthe in a coupe and discard any that immediately puddles. Double strain the drink into the coated glass. Gently dash the Peychaud’s over the top of the drink, trying to concentrate several dots in the center. Use a toothpick to draw the bitters out into a nebulous, heavenly shape. Discard the toothpick, pick up the glass, and get your drink on.

To make coconut syrup, heat up equal parts sugar and water to create a 1:1 simple syrup. Give it a stir and don’t let it boil. As soon as all the sugar is dissolved, add unsweetened, unadulterated, flaked coconut to the syrup and let it sit for about a half hour to an hour until your kitchen smells like coconut.

8 Black Friday Tips and Strategies

The competition among Black Friday bargains is expected to be brutal this year, with as many as 138 million shoppers trolling for deals that day. Gourmet Underground Detroit has come up with the following tips and strategies that will help you navigate the start of the holiday shopping season like a pro.

- Stay home and assemble a jigsaw puzzle while drinking whiskey.

- Stay home and cook a nice meal while drinking whiskey. Try to find a way to use whiskey in at least one of the dishes you are preparing. It looks better that way.

- Stay home and read a book about whiskey while drinking whiskey.

- Stay home and download hilarious and disturbing videos of people stepping on each other in order to buy things while you drink whiskey from the comfort of your sofa.

- Stay home and knit whiskey bottle cozies for holiday gifts while drinking whiskey. Careful, those needles can be pokey.

- Stay home and invite your friends over to drink whiskey. Make sure you tell them to bring some whiskey. (Pro tip: call this a “whiskey tasting”. It gives it an air of legitimacy.)

- Stay home and assemble a small distillation apparatus, preferably constructed with copper. Ferment a bit of corn, wheat, barley, or a combination of the three. Run this fermented wash through your shiny new distillation apparatus. Age resulting spirit in wood barrels. (We recommend that you drink whiskey during this process. But please avoid open flames while drinking whiskey.)

- Set your alarm for 3:30 a.m. Layer your clothing in case of frigid temperatures. Get in your car. Get out of your car. Stay home and drink whiskey.

Happy Thanksgiving!

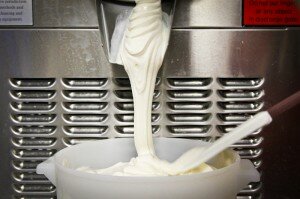

Bourbon Milk Punch Ice Cream

If you’ve followed Gourmet Underground Detroit for any length of time, you know that one of our favorite seasonal cocktails is Bourbon Milk Punch. It has qualities similar to eggnog without being thick and cloying, thus easier to consume multiple drinks if one is so inclined, as we usually are. Earlier this year, we suggested to Scott Moloney, owner and operator of Treat Dreams, that he turn this handsome drink into an ice cream flavor.

No amateur when it comes to crafting ice cream out of unorthodox (and occasionally bizarre) ingredients, Moloney was initially inspired to push boundaries after seeing the “challenging” San Francisco ice cream shop, Humphry Slocombe, make a prosciutto ice cream. Among his recent, most peculiar projects is a brown sugar ham ice cream that acquired its flavor from simmering the ice cream base with a ham bone and clove. In the works is a Thanksgiving layered concoction built with one part turkey ice cream, one part sweet potato ice cream, and one part cranberry ice cream.

No amateur when it comes to crafting ice cream out of unorthodox (and occasionally bizarre) ingredients, Moloney was initially inspired to push boundaries after seeing the “challenging” San Francisco ice cream shop, Humphry Slocombe, make a prosciutto ice cream. Among his recent, most peculiar projects is a brown sugar ham ice cream that acquired its flavor from simmering the ice cream base with a ham bone and clove. In the works is a Thanksgiving layered concoction built with one part turkey ice cream, one part sweet potato ice cream, and one part cranberry ice cream.

Ice cream flavored with alcoholic beverages seem mainstream in comparison.

Moloney has done plenty of liquored-up ice cream flavors before this project, as demonstrated by a well-stocked bar in the Treat Dreams kitchen. He has used beer, wine, mead, vodka, absinthe, Chambord, and lots of bourbon. He instructed us on just how much booze we could legally add — to a total of 4% by volume — and we went to work trying to replicate the flavor profile of the drink.

Moloney has done plenty of liquored-up ice cream flavors before this project, as demonstrated by a well-stocked bar in the Treat Dreams kitchen. He has used beer, wine, mead, vodka, absinthe, Chambord, and lots of bourbon. He instructed us on just how much booze we could legally add — to a total of 4% by volume — and we went to work trying to replicate the flavor profile of the drink.

The finished ice cream contains a healthy amount of Buffalo Trace Bourbon as the base flavor, a touch of St. Elizabeth’s Allspice Dram for a spicy and mildly bitter flavor kick, and a dose of fresh nutmeg for dreamy, floral aromatics. Success! It definitely tastes like the milk punch we make at home – which means it’s damn good.

The release of Treat Dreams’ Bourbon Milk Punch Ice Cream coincides with the opening of Planet Ant Theatre’s upcoming play, The Sunday Punch, a comedy that “explores the bewildering journey through aging, marriage, and family roles, while addressing the dangers of apathy and silence in the face of injustice”. Gourmet Underground wholly supports the arts and we figured this was as good a reason as any to finally bring life to this ice cream flavor.

The release of Treat Dreams’ Bourbon Milk Punch Ice Cream coincides with the opening of Planet Ant Theatre’s upcoming play, The Sunday Punch, a comedy that “explores the bewildering journey through aging, marriage, and family roles, while addressing the dangers of apathy and silence in the face of injustice”. Gourmet Underground wholly supports the arts and we figured this was as good a reason as any to finally bring life to this ice cream flavor.

Since Treat Dreams opened a little over a year ago, the energetic Moloney has carried out dozens of these promotional collaborations with other independent businesses. He’s used everything from nearby Pinwheel Bakery cinnamon rolls to Slows brisket to create local flavors and he obviously enjoys working with his fellow small business entrepreneurs. While some of these flavors might not have the mass appeal of vanilla and chocolate, it’s certain that anyone can find something to his or her liking at Treat Dreams. We wouldn’t be surprised if it were the bourbon milk punch.

Treat Dreams is open 1 p.m.-9 p.m. Sunday through Thursday, and 1 p.m.-10 p.m. Friday through Saturday. Bourbon Milk Punch Ice Cream will be available for purchase starting Friday, November 25th to correspond with the opening of The Sunday Punch at Planet Ant Theatre Hamtramck.

The Champagnes of Duval-Leroy

A few weeks ago, I had the opportunity to taste through a significant number of the champagnes produced by Duval-Leroy, all of which were new to me. The experience was particularly instructive, giving me a sense that Duval-Leroy has a defined style for their wines: clean, elegant, never too weighty, and delicately oaked.

Sadly, the night also illustrated a problem common to so many wine drinkers in Michigan: our distribution system.

This tasting was organized by a local customer. It was he, not the distributor, who negotiated the details of the event. Why? Because after trying to order the wines through the appropriate distribution channels and being ignored by the distributor — in this case, Great Lakes — he was fed up.

So he worked directly with the U.S. representative from Duval-Leroy, Arthur, who brought a killer line up of wines, some of which may be available in the coming months through local shops like Cloverleaf Fine Wine. (I know in the past that Elie Wine Company has also sold Duval-Leroy champagnes.)

Tasting Notes

Brut (Non-vintage): Unlike other moderately priced champagnes, this has real power. There’s a strong concentration of citrus and yeast flavors with a longer finish that one might expect from an entry level product. Plenty acidic, so a nice companion to food.

Rose Sec (Non-vintage): As Arthur explained, “sec” in champagne is a relative term. Of course, it means “dry,” but it’s dry compared to an older standard of dry versus sweet. In this case, the wine is in fact pretty sweet, not something I generally like. In this case, I find it a bit on the fat, unfocused side, but the flavors are quite rich and would seem to work well with dessert (though we drank it with fois gras and waffles).

Clos des Bouveries 2004: Arguably the biggest value (and surprise) of the night, this is unlike just about any champagne I’ve ever had. It’s fermented in oak, and it carries with it lots of structure and some of that toasted flavor. But it’s hardly oppressive. Indeed, the wine is brimming with fruit aromatics, it feels quite lively and crisp, and the finish is long. It glows in the glass, almost like a Riesling. Very interesting stuff. Retails for around $50, which is expensive for a lot of wines but pretty reasonable among champagnes, especially when one considers they might pay $45 for some terrible Veuve Cliquot.

Femme de Champagne 1996: This is their flagship, heavy hitter, and it’s crazy good. Even now, it tastes youthful with plenty of acid. But it’s layered with yeast, brioche, wood, and fruit. Complex and delicious. This vintage is nearly impossible to find, even online, but the 1995 and 2000 are both available (if the distributor is willing to get off its ass to place an order for you). It’s expensive stuff at $120+ per bottle, but the 1995 is supposedly similar to the 96, and if you’re ever looking to splurge a bit, this isn’t a terrible place to start.

Femme de Champagne 1996: This is their flagship, heavy hitter, and it’s crazy good. Even now, it tastes youthful with plenty of acid. But it’s layered with yeast, brioche, wood, and fruit. Complex and delicious. This vintage is nearly impossible to find, even online, but the 1995 and 2000 are both available (if the distributor is willing to get off its ass to place an order for you). It’s expensive stuff at $120+ per bottle, but the 1995 is supposedly similar to the 96, and if you’re ever looking to splurge a bit, this isn’t a terrible place to start.

Rose Brut: Beautiful pink color with a bit more fruit on the nose and a bit more rounded flavor profile than some of the other wines. Dry as a bone but finishes a bit short. A perfectly nice wine, especially if you “need” a rose, but for a similar price, I’m drinking the Clos des Bouveries every time.

Cuvee Paris 2006: An elaborate design wraps around this entire bottle. It’s a nice wine – tart, yeasty, minerally. Unquestionably more complex than the Brut NV, but for twenty dollars more, it’s definitely more for regular champagne drinkers. At the price, the Bouveries is again a more interesting drink to me.

– – – – –

Duval-Leroy is an interesting producer for reasons beyond the wines themselves: The company is family owned, as it has been since its inception in 1859. It’s dramatically larger than many of the tiny grower/producers, but it’s practically minuscule compared to the popular, behemoth brands like Veuve Clicquot or Moet. After tasting the wines, I think this offers them some advantages in terms of being able to produce bottles of both quality and value at scale.

To offer some perspective, here’s a rough comparison of production levels (figures pulled from a June 2nd article on Shanken News and a piece on small grower champagnes from Decanter):

- Moet & Chandon: Shipped 2.73 million cases (almost 33 million bottles) worldwide in 2010, not including its popular, high-end Dom Perignon brand

- Veuve Cliquot: Shipped 1.32 million cases (almost 16 million bottles) worldwide in 2010

- Duval-Leroy: Produces about 5 million bottles per year

- Larmandier-Bernier: Produces around 130,000 bottles per year

I included Larmandier-Bernier because (a) it’s located in the same area in which Duval-Leroy is headquartered and (b) it shows just how little the “little guy” in Champagne can really be. But it’s also quite a different animal altogether.

More appropriately, compare Duval-Leroy to Veuve: The entry level product for both producers runs in the neighborhood of $35. That’s being generous to Veuve, which is often sold for upwards of $40. In Michigan, both producers are distributed by Great Lakes. Unfortunately for consumers in Michigan, the distributor’s priority seems to be on mediocre yellow label from Veuve, which is a shame, considering:

- It tastes and smells like sulfur with sometimes bitter, very flat flavors

- Half their packaging probably costs more to make than the wine, so you have to ask what you’re paying for

- It’s yet another example of big business operating like you’d expect a lot of big businesses to operate

So what’s the point of all my rambling?

I suppose it’s three-fold: (1) If you’re interested in trying some reasonably priced champagne — not Cava or other sparkling wines, for which there are plenty of decent sub-$20 options — Duval-Leroy seems like an excellent place to get started. (2) Unsurprisingly, a mid-sized, family-owned producer is making drastically better products than large corporate producers at similar prices. (3) Always be aggressive with your retailers and your distributors, because as I’ve learned first hand watching this tasting come together, Michigan suffers from a flawed system in which distributors base their inventory on what they can sell with minimum effort rather than what they can sell to interested consumers.